The Workout Routine an 80-Year-Old Used to Train for the Ironman World Championship

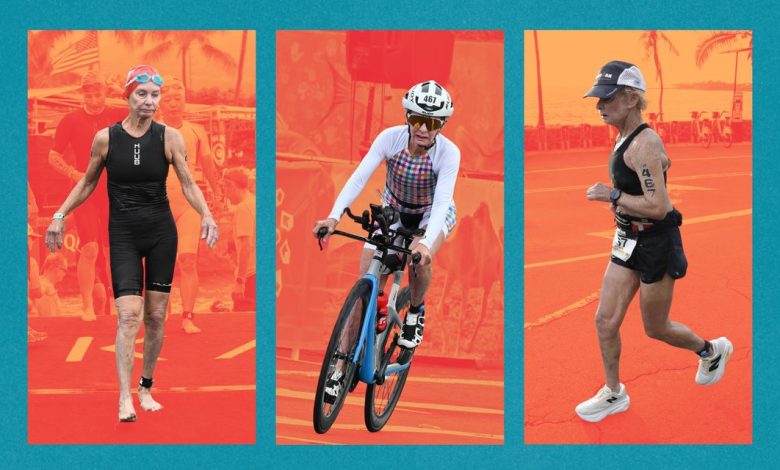

For most people—regardless of age—so much as attempting a triathlon is a daunting prospect, let alone actually completing one. Even more impressive would be finishing fast enough to officially rank. But that’s exactly what 80-year-old Natalie Grabow did at the 2025 Ironman World Championship in Kona, Hawaii, earlier this month.

On October 11, Grabow, an avid triathlete who took up the demanding athletic discipline at 59, became the oldest woman to ever complete an Ironman World Championship, breaking the previous record set by then 78-year-old Cherie Gruenfeld in 2022. She chugged across the finish line 16 hours, 45 minutes, and 26 seconds after starting—around 15 minutes shy of the 17-hour cutoff time.

To ask Grabow how she pulled off this historic achievement, SELF caught up with her over Zoom 11 days after Kona. “I think as you get older, it’s important to feel strong in your body, and then you feel strong in your head,” she tells SELF. “When you challenge yourself to do some hard things, it’s just a great feeling…. Even if you don’t do as well as the next person, you did as well as you could do, and you can’t ask more of yourself than to give everything you’ve got.”

Read on to learn how Grabow discovered a passion for triathlons later in life, what her training schedule looks like, and how she hopes her success inspires others to push their limits.

How she discovered a passion for triathlons

“I’ve always been competitive, and I’ve always enjoyed sports,” Grabow says, a bouquet of balloons emblazoned with celebratory messages (“You’re Number #1!”) bobbing in the background of her computer screen. During her early years in the 1940s and ’50s, however, she didn’t really have much of an outlet for that energy: Back then, sports teams for women and girls weren’t an option in school. “We had cheerleading to do, but that was about it,” she says. “We didn’t have sports like the boys had.”

Later in life, when she temporarily left the workforce to start a family, Grabow found more opportunities to explore her interest in fitness. She played tennis when her two daughters were young and turned to running shortly before she went back to work in her early 40s. Eventually, she progressed from short jogs during her lunch breaks into 5Ks and 10Ks locally. Encouraged by her runner friends, she entered a sprint triathlon, an entry-level race that consists of a half-mile swim, a 12.4-mile bike ride, and a 3.1-mile run: “They kept saying, ‘Come on, Natalie, there’s a sprint right in the next town. Come and do it,’” she says.

There was just one (big) problem: Grabow had never learned to swim. She came up with a workaround—one of her daughters subbed in for her during the swimming portion of the event—but knew what she’d have to do if she wanted to continue competing: learn how to swim for real. So at 59, she became a regular at her local YMCA pool. “That was scary. I was very, very awkward and slow and could barely get from one end of the pool to the other in the beginning,” she says. “But I was pretty determined. I wasn’t afraid of it. I just didn’t know how to do it.” Slowly but surely she improved, though the discomfort never totally left. Swimming “didn’t come naturally to me, it’s still not my favorite part, and I’m not that great at it, but I can get through it,” she says.

Just nine months after her first self-directed swimming lesson, in the spring of 2005, Grabow completed her first full triathlon: the New Jersey Devilman, another sprint. From there, “I was just hooked,” she says. Before long, she progressed to a half-Ironman (also known as a 70.3), and, finally, an actual Ironman, which involves a 2.4-mile swim, a 112-mile bike ride, and a 26.2-mile run in one fell swoop. Twenty years and 93 triathlons (including 16 Ironmans) have passed since Grabow’s triathlon journey began, but she’s still going strong—a sense of drive that stems in part from her early experience of exclusion. “I don’t feel like I’ll ever get tired or burn out of the sport because I didn’t have a chance to start early,” she says.

To train for Kona, which marked her 11th appearance at the Ironman World Championship, Grabow followed a punishing fitness regimen. Earlier in the race season, she had done three 70.3s, so she was already in solid shape, but she had to take her workouts to the next level to prepare for the heightened demand on her body. There wasn’t much margin for error: If she didn’t cross the finish line by the 17-hour mark, she’d be disqualified from the race and forfeit her bid for the oldest woman finisher title. One other woman in the 80–84 age group had previously tried and failed, so “I knew that was going to be a big challenge,” she says.

During training, every day followed the same routine. A self-described “very early-to-bed, early-to-rise person” who’s “nearly always asleep by nine o’clock [p.m.],” Grabow rose between 5:30 and 6:30 a.m. Breakfast came first, a nonnegotiable. “I just have to eat,” she says. “You have to pay attention to what your body demands and what feels good for you.”

Then, it was straight into stretching and mobility work—“anything to loosen tight areas up,” from foam-rolling to core exercises, Grabow says. Stretching is particularly important in her mind. “When I was younger, I might just go out for a run and not think about that,” she says. “But I think as you age, you have to really take care of your body in that way, [so] if something’s tight, make sure you get that nice and loose before you go for a run.” Drilling her glutes is also a priority for her. “You use your glutes so much in sports,” she says, so to keep those all-important muscles in peak condition, she made sure to incorporate targeted moves like hip thrusts.

After stretching, it was time for her primary workouts: runs, swims, and bike rides. Generally, Grabow aimed for two per day, mixing and matching modalities. Her coach, Michelle Lake of Fiv3 Racing, would in turn keep track of her distances—“the total number of miles I was running and the time on the bike and the yardage for the swim”—so Grabow could escalate slowly but surely, building the strength and endurance necessary for Kona.

In keeping with her philosophy that “food is very important,” Grabow ate consistently throughout the day to make sure she had enough fuel to perform her best, from small meals at home to energy gels on long runs or bike rides. “I eat about five times a day, every three to four hours, and I just eat what I feel like my body needs at that time, whether it’s protein or carbs or whatever,” she says. “I’m not a fussy eater and I don’t have a particular diet that I follow, so I include sweets and chocolate and all sorts of things.”

Outside of training, Grabow also had other commitments, including caring for her husband, who is “not doing that well physically.” “That’s part of my routine, to get him up, get him dressed, showered, breakfast and his meals and that type of thing,” she says. Then, of course, there are her two daughters and her grandchildren. But she didn’t have a problem managing her time: “I’m very organized and I don’t watch a lot of television, so it works out,” she says.

Swimming up to 3,800 yards

For her swims, Grabow returned to the place where she took her first tentative strokes all those years ago: the pool of her local YMCA. “My swims were three times a week, 3,300 to 3,600, 3,800 yards at a time,” she says. Since she came to swimming later in life, she only knows one stroke: the freestyle. When she reaches the opposite wall in the pool, she doesn’t do the classic flip turn, either. Instead, “I just touch the wall and go back,” she says. Describing herself as a “little slow” in the water, she estimates her swims took her around an hour and twenty minutes to an hour and a half on average.

Biking up to six hours

Grabow did her bike workouts in an indoor workout room at home, blasting fans and the AC unit to create the cool training conditions she prefers. “I have a power meter on my bike and my coach gives me a specific workout so that I do a certain interval of time at a certain power and then change that up,” she says. While biking, she listens to music on the radio, though the specific song doesn’t matter as long as “it’s got a good beat and it’s not rap or something.” “I don’t really pay attention to what I’m listening to,” she admits. “I’m really working very hard, hitting these power goals that my coach gives me.” If anything, “working very hard” is an understatement: Her bike workouts could stretch as long as five and half to six hours.

Running up to two hours and 20 minutes

Grabow likes to run outside, mainly on the soft, flat, forgiving surface of her local high school track. “I do two or three shorter runs during the week, 35 to 40 minutes, 45 minutes,” she says. Over the weekend, by contrast, she’d do a longer run interspersed with walking breaks. “I run maybe a mile and walk a minute and repeat that for up to two hours and 20 minutes,” she explains. Despite the hefty time commitment, her weekly run mileage never exceeded 20 miles, which she describes as “pretty low.” (Relatively speaking, of course.)

Grueling as this schedule may sound, Grabow is goal-oriented enough that she didn’t mind the hard work; rather, she saw it as a means to an end. She’d remind herself, “You’ve got to do this or else you’re not going to do so well in the race”—stakes high enough that she was able to “put aside that boredom and focus on what I need to do.” Besides, Grabow adds, there’s something deeply satisfying about giving a task your all, whether or not you manage to achieve the objective you had in mind. Unlike an award or title, “nobody sees that,” she reflects, “but just that feeling of being proud of your effort that day is what really motivates me.”

Going into the Ironman itself, Grabow felt pretty confident in her body. Plus, she had outside support: Not only did her coach turn out to cheer her on, one of her daughters did too, telling her, “Mom, you’re doing great.” Still, the tropical climate always poses difficulties. To avoid overheating and potentially dropping out, “it’s a matter of really listening to your body and staying cool,” she says. Near the finish line, she ran into another obstacle—literally. Skidding on a wrinkle in the carpet leading up to it, she face-planted right in front of the cameras. The resulting video clip “was shown over and over again the next day on Facebook. I couldn’t look at anything without seeing me fall.” Even though the incident was a little embarrassing for her, she didn’t let it mar her overall feelings about her performance. “I was a good 15 minutes before the cutoff, so that was a good cushion for me,” she says.

What’s next?

While Grabow may be competitive, her passion for triathlons is fundamentally rooted in something besides a desire for trophies and world records: her love of movement. Fully aware she might not succeed at Kona, she made a promise to herself beforehand: that she would celebrate the outcome no matter what happened. “I knew that there’d be a good chance that I wouldn’t make the cutoff and I didn’t want to go into it knowing that I’d be really disappointed,” she says. “[So I told myself] even if I don’t make it, that’s okay. ‘You did something hard, you tried something and no one else has done it, but you tried it and you should be proud of yourself.’” And when she actually succeeded? “I was just absolutely thrilled that I could do what I set out to do,” she says.

Not that Grabow is content to rest on her laurels. Far from it, in fact. Currently, she has two half-Ironmans lined up for next summer—and, maybe, just maybe, she tells SELF, her sights set on another world record someday. “The one woman who wasn’t able to finish Kona, [Madonna Buder], she holds the record for finishing an Ironman at the oldest age—she did Ironman Canada at 82—so now that’s a goal out there that I might try to pursue at some point,” she says. Seeing someone succeed at something is a powerful thing, especially when they don’t conform to the stereotypical image of success in that endeavor, whether by virtue of age, race, sex, ability, or any other trait. It sets a precedent; it shows you what’s possible; it broadens your sense of your own capabilities. “You say, ‘Well, she did it,’” Grabow reflects. “‘Maybe I could do it, too.’” Now, as the newly crowned record holder, she’s setting that same example for others.

Related:

- 9 Fitness Tips From Athletes in Their 90s (and Beyond!) Who Are Still Crushing It

- I’ve Tackled Triathlons, Marathons, and Mountain Races—All While Living With Crohn’s Disease

- I Race Ultramarathons Up to 100 Miles, and I Have Lupus. Here’s How I Train

Get more of SELF’s great service journalism delivered right to your inbox.